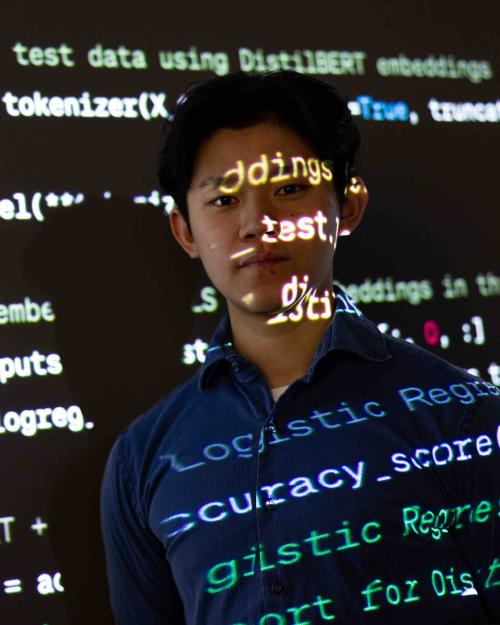

This semester, rather than banning the use of artificial intelligence (AI) for his assignments, three of Franklin Zheng ’25’s five professors actually required him to use it. It’s a trend happening in universities around the country, as AI becomes another research tool rather than something to be feared.

For Zheng, AI helped him analyze 70,000 court records to find themes, topics, keywords and general sentiment arcs. It came up with a list of best practices within the field of cyber security. And it responded to half of his weekly essays and assignments for a government class.

“When I ask it technical or coding questions, it can come up with simple algorithms and the code will run perfectly fine. It’s a game changer if you’re having it do this kind of busy work,” said Zheng, who’s majoring in information science and minoring in international relations and German studies in the College of Arts & Sciences.

“But when you’re writing an essay and try to incorporate ChatGPT, the amount of setup and prompting it takes to effectively use it nullifies the efficiency of using it,” he said. “In order for it to produce substantive and in-depth writing, you need to provide it with substantive and in-depth prompts. That takes more time than actually writing the essay.”

When ChatGPT and other generative AI platforms first became widely available, professors on many college campuses responded with understandable concern: How will students use this to cheat? How well can the tech write an essay? Can it come up with computer code or solve problem sets and show the steps? And how on Earth can we police this?

But with the arrival of easy-to-use generative AI tools last year, the questions have changed.

“I look at AI as another technology that has extended human capabilities in ways that eliminate a lot of drudgery,” said Matthew Wilkens, associate professor of information science in the Cornell Ann S. Bowers College of Computing and Information Science, who teaches one of Zheng’s classes this semester, “Text Mining for History and Literature.” “Just as workers were understandably concerned about steam power or electronic factory robots, in the end mostly what that created was a situation in which workers get to do more interesting things and things that are more significant.”

Cornell has issued preliminary guidelines for using AI, “which seek to balance the exciting new possibilities offered by these tools with awareness of their limitations and the need for rigorous attention to accuracy, intellectual property, security, privacy, and ethical issues.”

And a report issued September offers guidance for faculty. That report, a Cornell Chronicle story explains, addresses the ways in which these tools can customize learning for individual students – but may also circumvent learning, hide biases and have problems with being inaccurate.

Weighing the new research possibilities vs. AI’s drawbacks

For professors like Wilkens, the potential of AI is exciting.

“You used to need to be able to write some code to interact with a machine learning model, but now you can use a natural language prompt and expect to get a meaningful answer,” said Wilkens, who has a diverse background in chemistry, philosophy and comparative literature. “That’s super cool and promising to allow more people without a lot of tech training, but with interesting humanities questions, to be able to answer those questions.”

For Sabrina Karim, the Hardis Family Assistant Professor in the government department (A&S), it was important for students in her seminar on gender and politics to begin the semester reading about gender and racial biases embedded in generative AI before experimenting with it in their essays. Over the course of the semester, the class has experimented with different prompts, especially as they relate to research papers versus personal essays.

“There will be big changes in the world – we’re already seeing that in many industries,” Karim said. “My goal is to instill how we can use this ethically and responsibly in a way that will help students in their careers.”

Kannah Greer ’24, a government major in Karim’s class, said she’s learned a great deal about the importance of using creative and specific prompts when working with AI.

“While I do not trust AI enough to depend on it for fact-based answers, I often use it and plan to continue using it to brainstorm ideas and concepts that I may have otherwise overlooked or not even known about,” she said. “You are only limited to what you know, and often, students looking to expand their ideas are limited to the knowledge of their professors, but AI has virtually no limits to what can be known and built from.

“As someone who is always looking for equitable solutions to pertinent social problems, it is exciting to have a tool to bridge my analytical analyses with creative solutions.”

In classes taught this semester by Peter Katzenstein, the Walter S. Carpenter, Jr. Professor of International Studies (A&S), students are experimenting with ChatGPT as a research tool, asking it questions about international relations theory and determining its possibilities and limitations. They’re also using ChatGPT as an interlocutor, someone you might ask to read and respond to your work. And they compose arguments and counterarguments on world political issues, ask AI to do the same and then compare their work.

In each case, students include an appendix to the assignment, explaining their interactions with ChatGPT, what they thought it did well and where it fell short, all backed up with transcriptions of their chats.

“We have conversations about what these large language models tend to be really good at, and where students need to be more careful,” said Amelia C. Arsenault, a graduate student in the field of government who is a teaching assistant in Katzenstein’s classes.

“We’re giving them a toolkit so that they can determine whether what they’re being offered by ChatGPT is actually good enough for their work,” said Musckaan Chauhan, another grad student and teaching assistant in Katzenstein’s classes.

Focusing on the 'gorgeous sentences'

In Cornell first-year writing seminars, Tracy Carrick, director of the Writing Workshop in the John S. Knight Institute for Writing in the Disciplines, works with students to experiment with ChatGPT in class and during individual conferences.

By comparing their work with AI-generated text, students are able to see some of AI’s shortcomings: clunky transitions, generic text, no citations, lack of sentence length variation, awkward flow, inherent biases, hallucinations (coming up with false information) and poor paragraph development, among other problems.

“It ignores a lot of the lessons we go through in class, including those about crafting your own voice and building your ideas alongside of and with those of others,” Carrick said.

An AI bot also can’t address your audience with the same care and intention you would, Carrick said, nor can it incorporate material from class discussions, not without considerably adept and attentive prompt engineering.

Many students, Carrick found, noted that generating prompts for their writing assignments was considerably less pleasurable and a lot more work than writing the assignment from the ground up themselves.

But Carrick does find it useful for conducting research. When brainstorming a way to frame a topic, refining search terms, and even locating sources, ChatGPT can uncover more interesting and unique information than a normal Google Search, she said, especially when using the premier (paid) version.

It cannot replace traditional strategies, she’s discovered with students, but it can be a good way to access information about new topics.

When it comes to their drafts, ChatGPT can craft boilerplate text or sentences that aren’t terribly essential or important to the flow or meaning of your work, she said.

“This is one of many tools for students and they can use it ethically and strategically in ways that are supportive of their ideas and their voice without feeling that they aren’t good enough to do this writing on their own,” she said. “It’s similar to the predictive text that comes up when you’re typing a text message or using GoogleDocs. If that one sentence isn’t important, but it allows you to spend time crafting 5-6 really gorgeous sentences, then I’m more than OK with that.”

Carrick’s worries about ChatGPT focus less on policing and more on access to the platform (there’s a free version but the $20/month version is better) and on its impact on students’ ability to work through their original “messy ideas” when creating first drafts.

The future of AI for classrooms, careers

Tracy Mitrano, senior lecturer in information science, said her classes will continue to integrate more and more AI discussions. This semester, students in her “Law, Policy and Politics of Cybersecurity” class used AI for research into cybersecurity issues related to AI, and also compared and debated the effectiveness of AI regulation in the U.S. and the European Union. Next semester, she’ll be teaching “Law, Policy and Politics of AI in the World,” completely focused on AI’s impacts in those spheres.

“This is a quantum level change, not unlike the invention of the printing press and then the internet,” she said.

The impacts for the future of work and the labor market are also massive, she said, comparing the introduction of AI to the free trade agreements that allowed many companies to outsource work to other countries 30 years ago.

“This is not a problem of technology or AI,” she said, “the real problem is government and deciding what ways we may or may not think the government should be involved in regulating it.”

For Zheng, though he’s impressed with AI’s abilities, he thinks his actual human skill set will still be needed in the field he’s considering.

“I don’t want to do software engineering or web development. I’m more interested in working in data analysis or foreign policy,” he said. “That work involves acquiring data from a number of outside sources (like diplomatic documents, economic reports and real-time data) and ChatGPT is constrained by the mediums it can take in for information.

“But when they breach that gap, then …”